A Summary of the Court of Appeal’s Judgment in Thatchers v Aldi

Tim Heaps, ‘Cloudy Outlook for Copycats? Successful Reputation-based Trade Mark Claim in Lookalike Packaging Dispute: A Summary of the Court of Appeal’s Judgment in Thatchers v Aldi [2025] EWCA Civ 5 Issue 142 (December) Intellectual Property Forum, page 57.

In January 2025, the Court of Appeal (England & Wales) (“CoA”) overturned the first instance decision of the Intellectual Property & Enterprise Court (“IPEC”) in Thatchers v Aldi finding that discount supermarket Aldi’s use of lookalike labelling for its lemon cider product took unfair advantage of Thatchers’ reputation in its trade mark relating to its own lemon cider variant.

The case forms part of a growing number of disputes in the United Kingdom (“UK”) and globally concerning the use of lookalike packaging, typically by discount retailers seeking to mimic the get-up of well known brand products and generally push the boundaries of acceptable imitation and competition.

The outcome serves as a worthwhile reminder that it is possible for brand owners to succeed with trade mark infringement claims against lookalike products, even in circumstances where there is no likelihood of consumer confusion. In particular, reputation based claims alleging unfair advantage are particularly effective where the brand owner has taken steps to register trade marks covering the distinctive aspects of its product packaging.

Background

The claimant, Thatchers, is the largest family-run independent cider producer in the UK. In February 2020, Thatchers launched its “Cloudy Lemon Cider” variant, selling it in individual 440ml cans in four-can packs with cardboard packaging. Thatchers extensively promoted the new product and it sold well.

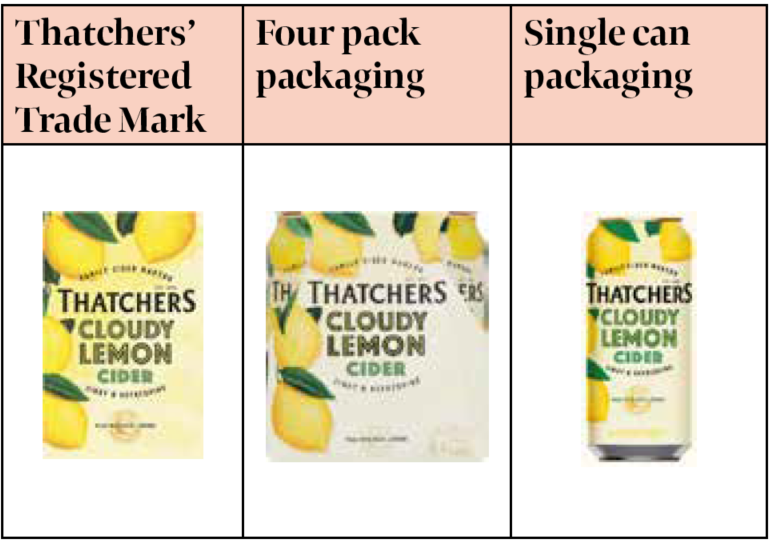

Notably, Thatchers filed and registered a device trade mark depicting the front label of the Cloudy Lemon product, which featured on the front and rear of each can (the “Trade Mark”). It was also reproduced in a slightly modified form on the front, rear and top of the cardboard packaging for the four-can packs.

Images of the Trade Mark, together with the four-pack packaging and single can packaging are shown below.

The defendant, Aldi, is a well known discount supermarket. Aldi’s business model involves an emphasis on own-brand products which are often packaged in a way that closely mimics the packaging and/or branding of well known brand products.

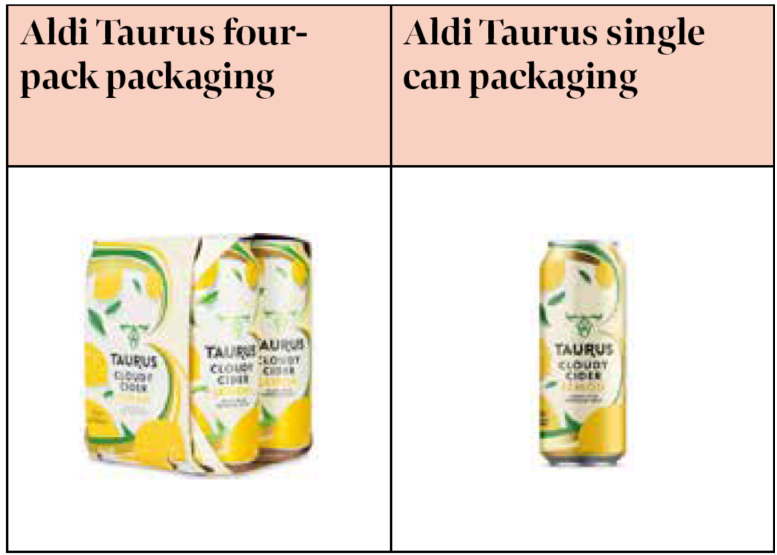

In May 2022, Aldi launched its “Taurus Cloudy Lemon Cider” product, which was sold in 440ml can four-packs with cardboard packaging. Like the Thatchers product, the Aldi Taurus product had a design which featured on the front and rear of each can, which was also reproduced almost identically on the front and back of the cardboard packaging.

Aldi’s internal evidence at trial showed it had instructed its design agency to use the Taurus product as a “benchmark” and create “a hybrid of Taurus and Thatchers” when designing their packaging.

Images of the four-pack and single can packaging are depicted below.

High Court Proceedings

In September 2022, Thatchers commenced proceedings in the IPEC against Aldi for trade mark infringement under section 10(2) and 10(3) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (UK) (“TMA”) and passing off.

In 2024 the IPEC dismissed all the claims on the following summarised grounds:

- On section 10(2), the judge considered there to be no real likelihood of confusion (as required for successful 10(2) claims), primarily on the basis the additions to the Taurus packaging resulted in a “low degree of similarity” with Thatchers’ trade mark.

- On section 10(3), while the judge accepted that Aldi’s product would call the Thatchers’ Trade Mark to the mind of the average consumer (i.e. the requisite “link” for successful claims under 10(3)), it rejected the claim on the basis Aldi did not take unfair advantage of Thatchers’ mark or cause detriment.

- On passing off the judge found no misrepresentation had occurred.

The Appeal

While accepting the judge’s decision with respect to section 10(2) TMA and passing off Thatchers contested the IPEC’s dismissal under section 10(3) TMA with the CoA allowing permission to appeal that aspect of the IPEC judgment.

A summary of each of the key grounds for appeal permitted by the CoA and its conclusions relating to the same is set out below.

By way of background, section 10(3) TMA requires the following conditions to be satisfied din order to establish infringement under this provision:

- The claimant’s trade mark must have a reputation in the UK.

- The use must be in the course of trade in relation to goods and services.

- The defendant’s sign must be identical or similar to the claimant’s trade mark.

- The use of the sign must give rise to a “link” in the mind of the average consumer to the claimant’s trade mark.

- The use of the sign must give rise to injury in the form of unfair advantage, detriment to the distinctive character of the trade mark or detriments to the repute of the trade mark.

- The use must be without due cause.

Grounds for Appeal and the Conclusions of the CoA

What is “the sign” for the purposes of the infringement analysis?

Thatchers contended that the IPEC judge had wrongly identified the defendant’s “sign” to be the overall 3D appearance of a single Taurus cider can, rather than the 2D graphics printed on the front and rear of the can and the cardboard packaging. The CoA agreed, which in turn had important implications for the similarity assessment (see below).

Similarity between the Sign and the Trade Mark

Thatchers further challenged the IPEC judge’s conclusion that the degree of similarity between the defendant’s sign and the Trade Mark was “low”. This was on the basis that, among other things, the judge had made its assessment based on the incorrect comparison between a 3D design (the Taurus can) as referred above, and the device Trade Mark which was 2D. Again, the CoA agreed, observing that the 3D vs 2D comparison was not, in fact, a point of difference.

Further, the CoA considered the judge had been wrong to disregard the way in which Thatchers had used the Trade Mark, emphasising that the similarity assessment must consider the notional and fair use of the Trade Mark (i.e. how Thatchers had used it on its cans) and noting that the registered mark being 2D does not detract from comparing it to a 3D packaging design.

The intention of the defendant

A central part of the CoA’s reasoning concerned Aldi’s intention and whether the use of the sign constituted “unfair advantage”. While proof of intention is not necessary or determinative when establishing infringement, it is still of evidential relevance.

Thatchers considered that the IPEC judge’s analysis of Aldi’s intention was flawed don the basis the judge had confused an intention to take advantage of the reputation of the trade mark (which is relevant to section 10(3) infringement) with an intention to deceive (which is relevant to section 10(2) infringement.

The CoA concurred, and when re-assessing the judge’s findings sin view of this came to the ‘inescapable conclusion’ that Aldi had indeed intended the sign to remind consumers of Thatchers’ Trade Mark and to convey the message the Aldi product was like the Thatchers product only cheaper, thereby taking advantage of the reputation of the Thatchers Trade Mark.

This conclusion was supported by (i) the fact that the Aldi lemon cider product significantly departed from the house style for its other Taurus flavoured ciders, (ii) the imitation by Aldi of the faint horizontal lines in the Thatchers product, with the replication of such “inessential details” often indicating copying; and (c) the design process revealed by the documentary evidence, which showed that Aldi’s brief to its design agency was to use the Thatcher product as a ‘benchmark’ and create a “hybrid of Taurus and Thatchers”.

While intent to take unfair advantage is not an essential criterion for infringement, evidence of the same is certainly beneficial to claimants in section 10(3) claims, with the CoA’s finding of intent a significant contributing factor in the CoA’s re-assessment of the IPEC’s finding of no unfair advantage.

Unfair advantage

Central to Thatchers’ appeal was its contention that the judge was wrong to conclude that Aldi’s use of the sign had not taken unfair advantage of the reputation of the Trade Mark.

In addition to the re-assessment of the IPEC’s conclusions regarding intent (see above) Thatchers’ additionally criticised the judge’s failure to address its case that Aldi’s use of the sign had resulted in a ‘transfer of image’ of the kind described by the Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”) judgment in L’Oreal v Bellure (C-487/07). Namely, that Aldi’s use of the sign was intended to remind consumers of the Trade Mark in order to convey the message that the Aldi product was like the Thatchers product, only cheaper.

The CoA considered the IPEC judge’s failure to give any consideration to this point to be an error of principle, finding that the case did in fact fit squarely within the description of image transfer in L’Oreal v Bellure. Among other things, the CoA pointed to substantial sales of the Aldi product in a short period of time without spending money promoting it and the evidence showing Aldi’s intention to take advantage of the Trade Mark’s reputation.

No finding of detriment to reputation

Interestingly, while unfair advantage was established, the CoA did not agree with Thatchers that Aldi’s sign also resulted in detriment to their Trade Mark’s reputation.

Thatchers had argued that the claimed inferior taste of the Aldi product would tarnish the reputation of its own mark since consumers would think that the Thatchers product had a similar taste profile It also claimed that the “Made with premium fruit” statement on the front of the Aldi pack (which was questionable) would be liable to tarnish Thatchers’ reputation, since consumers would then doubt the statement on the Thatchers’ product that it is “Made with real lemons”.

The CoA gave short shrift to these arguments, concluding that consumers would not make (negative) judgements about the Thatchers product simply because the Aldi product was arguably of lower quality and/or because the Aldi product made alleged unsubstantiated claims about its ingredients.

Honest descriptive use defence

Aldi advanced the defence under section 11(2)(b) TMA that certain elements of its sign (lemons, leaves, yellow colour) were descriptive or common in the market (i.e. for lemon-flavoured cider) and that it used them honestly. The IPEC judge had accepted that rationale.

However, the CoA rejected the defence. It held that Aldi could not dissect the sign into constituent elements and apply the defence to those elements alone in a vacuum. The sign as a whole must be considered; and in this case, the overall impression of the graphics went beyond merely describing lemon flavour The CoA held that the use of the sign was not in accordance with honest practices in industrial or commercial matters because Aldi was engaging in unfair competition (i.e. taking advantage of Thatchers’ investment).

Invitation to depart from L’Oreal v Bellure

Following Brexit, the CoA has the power to depart from decisions of the CJEU. Aldi invited the CoA to do so in relation to the CJEU’s ruling in L’Oreal v Bellure on the subject of unfair advantage, in the event its other arguments failed. The CoA declined citing multiple reasons, including a reminder of the importance of UK trade mark law remaining harmonised with EU law and the considerable legal uncertainty that would be created by departing from an important ruling.

Key Conclusions and Analysis

Typically in lookalike packaging cases, copycats use an entirely different brand name for the product in question as was the case here. Historically this has made establishing a likelihood of confusion under section 10(2) TMA or an actionable misrepresentation in the context of a passing off claim very difficult.

This case therefore serves as a worthwhile reminder that, even where there is an absence of actual or likely consumer confusion, brand owners do have other options for enforcing their rights against ‘dupes’.

Namely, reputation based trade mark infringement claims on the grounds of unfair advantage, where competitor use of similar packaging is aimed at benefitting from the trade mark owner’s investment.

A number of important lessons are worth highlighting from the case itself, which can be summarised as follows:

- It is essential that brand owners secure trade mark protection for product packaging and labelling – without such registrations, trade mark claims against lookalikes will be much more challenging. Since 10(3) claims are only available in relation to trade marks with a reputation, it is similarly important for brand owners to try and ensure the packaging they are seeking to protect has distinctive design elements.

- Brand owners and their representatives should take care when pleading their case to ensure the defendant’s “sign” is properly identified and defined and isn’t limited to e.g. the appearance of the competitor product in its 3D, since that approach can raise issues when seeking to establish similarity between the trade mark and sign.

- Similarity can be established between a trade mark for a product label and a sign, even when the individual elements featuring on the mark have low levels of distinctiveness. In this case, many of the elements were arguably somewhat descriptive or commonplace (e.g. images of lemons), but where the trade mark owner is able to establish its label registration has a reputation which is distinct from its brand name, those elements with low distinctiveness should not be disregarded when assessing similarity.

- While not determinative or strictly required, proving the copycat’s intention to take advantage can be an important factor in any successful claim. Evidence which will help demonstrate that intent includes:

a. Evidence of the defendant “benchmarking” the brand owner’s design when design its own product.

b. Evidence that (particularly minor) aspects of the brand owner’s design covered by the trade mark have been mimicked on the defendant’s packaging.

c. Evidence that the design of the defendant’s product significantly differs from the “house-style” of other products in the same product range (in this case, Aldi’s lemon cider product looked entirely different to the other flavoured ciders).

5. In contrast to unfair advantage claims, establishing detriment to repute in lookalike packaging cases is much more difficult and is unlikely to succeed based purely on a contention that the lookalike product is of inferior quality.

The Supreme Court’s refusal to provide Aldi with permission to appeal the CoA judgment in June 2025 brings the long running dispute to an end, and serves as a further endorsement of the reputation based trade mark rights available to brand owners against lookalikes.

Whether copycats will start to take a more cautious approach to their designs following the judgement remains to be seen, but the CoA reversal of the IPEC decision will nevertheless provide encouragement to brand owners that there is scope for success against lookalikes provided they have sufficient trade mark registrations in place.

/Passle/5f3d6e345354880e28b1fb63/MediaLibrary/Images/2025-09-29-13-48-10-128-68da8e1af6347a2c4b96de4e.png)

/Passle/5f3d6e345354880e28b1fb63/SearchServiceImages/2026-03-06-16-52-53-709-69ab0665a022d0ccd15c116a.jpg)

/Passle/5f3d6e345354880e28b1fb63/SearchServiceImages/2026-03-06-11-05-47-874-69aab50bed43be71de5d424c.jpg)

/Passle/5f3d6e345354880e28b1fb63/MediaLibrary/Images/2024-08-23-11-31-07-354-66c872fb971eecc249d83d40.png)